Economic Inequity, Black-on-Black Crime & Reparations

Economic Inequity, Black-on-Black Crime & Reparations

Economic Inequity, Black-on-Black Crime & Reparations

Let’s talk about economic inequity, Black-on-Black Crime & Reparations for just a moment. There is often talk of reparation among Blacks with very little understanding of its meaning, its challenges, and its demand upon those who desire it. First of all, it must be understood that reparations cannot be viewed as a moral issue — for this nation is not founded upon moral turpitude or else slavery, and Jim Crow would have never existed. Reparations must be confronted from a social and political perspective with an understanding of geopolitical mechanisms and influences.

When viewed properly, reparations should be viewed as the third phase of the Black sojourn in America, with slavery and Jim Crow as the first two. It must also be understood the very mechanisms that toppled the first two left us at a disadvantage in pursuing the third, but these same mechanisms must now be revisited.

While Blacks are commonly misled to believe that slavery and Jim Crow were defeated solely on American ideology and paradigm shifts, the truth is that our ancestors were effective in creating international alliances through which political pressure was applied to the American power structure in a way that forced its hand.

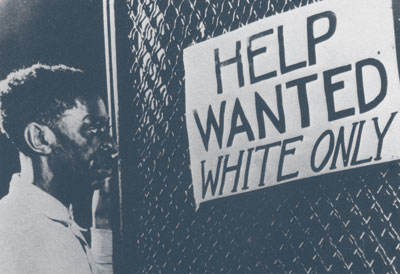

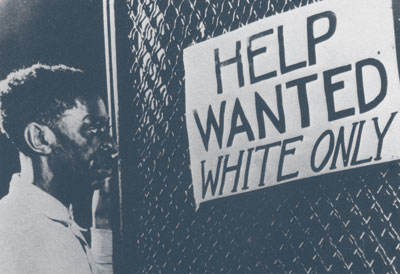

For instance, the cold war pitted the United States in a political-ideological struggle with the Soviet Union, and it would have been impossible to convince the world (Especially Afrocentric countries on the upswing) that the U.S. political ideology would be ideal when they were treating their citizens of color so poorly. So, the need to win the cold war and emerge as the World’s first singular superpower weakened the grip of Jim Crow segregation.

Unfortunately, when the original version of Jim Crow died, the international pressure subsided, allowing most of White Americans to move to the right (conservatism), which it has continued to do with increasing aggression, leading to the rise of the New Jim Crow.

This conservatism has made the talk of reparations a highly controversial issue, and it will require the Black who possess mobility to engage international allies to crank up the pressure once again. The mention of conservatism should be interpreted as an endorsement for liberalism, which is simply a different head on the same monster. Let’s take a look at a couple of socioeconomic influences that must be understood to clearly see the need for reparations for ADOS.

Economic Equity

Economic equity is a concept that focuses on the idea of economic equality and fairness among social groups and racial enclaves. Most references to economic equity are heavily centered on taxation and welfare economics; however, when discussing this concept in light of the racial caste system in the United States — especially at it pertains to Blacks and Whites, one must consider the multitudinous mechanisms created to ensure that economic equity for Blacks is never achieved. Redlining, urban renewal, benign neglect, and miseducation are just some of the institutionalized systems used to Block Blacks from effectively generating wealth.

When discussing reparations, it is immensely important to understand what is being repaired that warrants the payment that is being demanded. Without question, Whites gained an unfair economic advantage over the 246 years of chattel slavery where they did not pay for labor while not allowing Blacks to participate in reaping the benefits of their labor. After freed slaves and their descendants, hereafter referred to as American Descendants of Slaves (ADOS), they never achieved equal economic footing or allowed to accumulate wealth. Specifically speaking, there has never been a fair an equitable division of the wealth.

Systematic inequity is at the root of the economic enigma that has sidelined the majority of Black ADOS families. In addition to the aforementioned structural mechanism that blocked the building of Black wealth, we must also consider income inequality as it pertains to Whites and Blacks. While income and wealth are distinctive and income does not constitute wealth. The presence of disposable income can be a resource to acquire wealth.

Wealth among Blacks is more concentrated than income — meaning that many Black households have little to no cash in reserve accounts for emergencies. In 2016, only 20 percent of Blacks owned 64.9 percent of the wealth; however, this same group only received 52.6 percent of all Black income. In other words, income is disbursed more broadly than wealth in the Black community.

To look slightly deeper at the phenomenon that inhibits Blacks from effectively building wealth in the U.S., we can observe systematic obstacles such as tax codes that favor certain assets over others. For instance, 401(k) plans, IRAs, and mortgage borrowing to finance a primary residence receive preferential treatment under current tax codes. Unfortunately, Blacks are less likely to work for companies that offer retirement benefits like retirement savings due to historical occupational segregation. Additionally, Blacks are less likely to be homeowners as a result of systematic housing and mortgage discrimination.

The wealth gap between Whites and Blacks is reflective of the distinctions between both debt and assets. It is important to develop a lucid perspicacity of how the development of wealth is accomplished. For example, the belief that simply earning more will close the wealth gap is a fallible idea. Higher education and increases in wages come with some benefits and relief; however, these financial components are insufficient to close the wealth gap.

Black-on-Black Crime

You may be wondering what does Black-on-Black crime have to do with reparations. First, Black-on-Black crime is a myth propagated by mainstream media. Yes, Blacks commit crimes against other Blacks, but this is not some exclusive phenomenon as the term Black-on-Black crime suggests. I address this in detail in Addressing the Black on Black Crime Argument. The truth that most violence is proximal — meaning that people tend to harm and kill those they live near. The segregated social makeup of this country ensures that most racial groups reside amongst themselves — especially those who are impoverished. FBI statistics revealed that Whites commit 84 percent of White homicides. These numbers are true among all groups.

While the homicide rates of Blacks killing Blacks is slightly elevated, that increase can be explained by the poverty in the areas that these murders are occurring. Here lies the connection between what is referred to as Black-on-Black crime and the wealth gap. There are three primary ways to earn a living:

- Earn a wage (as an employee, business owner, or investor)

- Government subsidies (qualify for some social program which is never sufficient to support a high quality of life)

- To participate in the world of crime in some way

Poverty, as a result of high unemployment rates, among other factors, ensures a rise in crime, regardless of racial affiliation. The crime drives down property values, increases arrests (feeding the Private Prison Industrial Complex [Mass Incarceration]). As property values go down, investors come in to renovate and renew the area. Because of the decline in property value, these investors acquire real estate at pennies on the dollar.

As investors renovate and bring in new business, stores, and shops, the property value skyrockets. Because the original residents, Blacks, cannot afford the increased taxes on their property they are either foreclosed on or bought out. This form of forced displacement has become so common around the country that it is now referred to a serial forced displacement, and it has its own set of negative consequences for Blacks.

Violent crime is the result of orchestrated poverty, and it serves as a mechanism within the system that ultimately dislodges Blacks and forcefully takes what little property they have acquired. You must understand that the systematic oppression of slaves and the ADOS extended far beyond 1865 when Blacks received their quasi-emancipation.

A Superficial Look at Reparations

For more than two decades, I have studied the need for reparations for Blacks. The one common denominator is consistent and forceful systematic oppression. We have the work of Dr. Joy DeGruy, Douglas A. Blackmon, Dr. Na’im Akbar and many more who have compiled a wealth of pragmatic and empirical data that outlines the psychological and social impact of slavery and extended traumatic experiences that followed.

Dr. Claud Anderson, Michelle Alexander, Dr. Alexander Hamilton, and Dr. William Darity have gone to great lengths to explain the economic demand for reparations. What ADOS or African Americans have to understand is that reparations are meant to finance the repair of something that has been damaged by a particular government or group of people. What we are attempting to repair in the Black community extends 154 years out of slavery. The 12 years after the quasi-emancipation of slaves, known as the reconstruction era was actually the South reestablishing its antebellum reality. This era was when clandestine groups like the KKK reigned in terror. There were the Black Codes, Convict Leasing, Jim Crow Segregation, redlining, urban renewal, benign neglect, Co-Intel Pro, The War on Drugs, Mass Incarceration, gentrification, and more. These successive mechanisms not only inhibited the development of wealth by Blacks, but it also facilitated the multigenerational transmission of trauma. In my book, Born in Captivity: Psychopathology as a Legacy of Slavery, I discuss in detail the perils of traumatic reinjury as it can be traced across generations. There is a need for emotional and psychological healing that Blacks have yet to experience collectively.

Some estimate that economic reparations for ADOS should exceed $14 trillion. A number that large can create a cataclysmic shift in the battle for wealth. If only 30 percent of the current Black population optimized their share in reparations funds, that would be 13.5 million Blacks operating from a financially autonomous platform. It would change the game.

Just remember that it is not only about the money that was never paid to our ancestor for the work the did for free. It is for every wrong committed by this government and Whites that has produced a lingering effect. It is time for the United States to cut the check.

Click here to support the Black Men Lead rite of passage program for young Black males!

Click here to get your copy of my latest book, Born in Captivity: Psychopathology as a Legacy of Slavery at

Bibliography

Abraham, C. (2014). Transmission of Trauma 3. Dublin Business School.

Akbar, N. (1976). Chains and Images of Psychological Slavery. Tallahassee, FL: Mind Publications & Associates, Inc.

Akbar, N. (1991). Mental Disorders Among African Americans. African World Press.

Akbar, N. (1996). Breaking the Chains of Psychological Slavery. Tallahassee, FL: Mind Productions & Associates, Inc.

Alexander, D. R. (2010). What’s So Speical About Speical Education? A Critical Study of White General Education Teachers’ Perception Regarding the Referral of African American Students to Special Education Services. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

Alexander, M. (2010). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the age of Colorblindness. New York City: New York Press.

Anderson, C. (1994). Black Labor, White Wealth. Bethesda, MD: Powernomics Corporation of America.

Anderson, C. (2001). Powernomics. New York: Powernomics Corporation of America, Inc. .

Balbin, T. (2018, February 2). Breaking Down The Walls of Social Conditioning. Retrieved from Warrior. Do: https://www.warrior.do/social-conditioning/

Bennett, D. M., & Fraser, M. W. (2000). Urban Violence Among African American Males: Integrating Family, Neighborhood, And Peer Perspectives. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 93-117.

Berneys, E. (1928). Propaganda. Brooklyn, NY: IG Publishing.

Blackmon, D. A. (2008). Slavery By Another Name. New York: Random House.

Blanchett, W. (2006). Disproportionate representation of African American Students in Special Education: Acknowledging the Role of White Privilege and Racism. Educational Researcher, 24-28.

Boykin, A., & Toms, F. (1985). Black Child Socialization: A Conceptual Framework. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

DeGruy, J. (2005). Post Traumatic Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing. Portland, OR: Uptone Press.

Dick, D. M., Riley, B., & Kendler, K. (2010). Nature and Nurture in Neuropsychiatric Genetics: Where do We Stand? Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 7-23.

Dwyer, K. (1994). Testimony on Preventing School Violence and Effective Methods for Improving School Safety. National Association of Psychologists.

Edwards, O. W. (2006). Special Education Disproportionality and the Influence of Intelligence Test Selection. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 246-248.

Fullilove, M. T., & Wallace, R. (2011). Serial Forced Displacement in American Cities 19-1916-2010. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, Vol. 88, No. 3, 381-382.

Gregoire, C. (2014, December 28). How the Effects of Trauma Can be Passed Down From One Generation to the Next. Huffington Post.

Grier, W. H., & Cobbs, P. M. (1968). Black Rage. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishing.

Hanks, A., Solomon, D., & Weller, C. E. (2018). Systematic Inequality: How America’s Structural Racism Helped Create the Black-White Wealth Gap. Center for American Progress.

Harry, B., & Anderson, M. G. (1995). The Disproportionate Placement of African American Male in Special Education Programs: A Critique of the Process. Journal of Negro Education, 602-619.

Hilliard, A. (1980). Cultural Diversity and Special Education. Exceptional Children, 584-590.

Irging, M. A., & Hudley, C. (2005). Cultural Identification and Academic Achievement Among African American Males. Journal of Advanced Academics, 676-698.

J. Truman, M. R. (2010). Criminal Victimization. Bureau of Justice Statistics (U.S. Department of Justice).

Johnson, T. T. (2012). The Impact of Negative Stereotypes & Representation of African-Americans in the Media and African American Incarceration. University of California Los Angeles.

Jr., M. H. (2010). The Impact of Racial Trauma on African Americans. The Heinz Endowments.

Kardiner, A. (1941). The Traumatic Neurosis of War. New York: Hoeber.

Kolk, B. A. (2001). Exploring the Nature of Traumatic Memory: Combining Clinical Knowledge with Laboratory Methods. Trauma and Cognitive Science Haworth Press, Inc.

Kolk, B. V. (1987). Psychological Trauma. American Psychiatric Press.

Kolk, B. V. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Penguin Publishers.

Leary, J. D. (2001). Trying to Kill the Part of You That Isn’t Loved. Portland State University.

Miller, C. T. (1993). A Study of the Degree of Self-concept of African American males, in Grades Two through Four, in all-male classes taught by male Teachers and African-American Males in Traditional Classes Taught by Female Teachers. Dissertation Abstracts International.

Staff, E. (2003). Psychological Treatment of Ethnic Minority Populations. Society of Indian Psychologists, 13-18.

Stenvenson, H., Herrero-Taylor, T., Cameron, R., & Davis, G. (2002). Mitigating Instigation: Cultural Phenomenological Influences of Anger and Fighting Among “Big-Boned” and “Baby-faced” African American Youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence.

Stevenson, H. C. (2006). Parents’ Ethnic-Racial Socialization Practices: A Review of Research and Directions for Future Study. American Psychological Association, 1-24.

Stevenson, H. C. (2015). Development of the Teenager Experience of Racial Socialization Scale: Correlates of Race-Related Socialization Frequency from the Perspective of Black Youth. The Journal of Black Psychology.

Thompson, A. (2014). Scientific Racism: The Justification of Slavery and Segregated Education in America. Texas A&M University, 2.

Unknown. (2008). Resilience in African American Children and Adolescents: A Vision of Optimal Development. American Psychological Association.

Wallace, R. (2014). Epigenetics in Psychology: The Genetic Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma in African Americans. The Odyssey Project Journal of Scientific Research.

Wallace, R. (2014). The Emascualtion of the Black Man in America. The Odyssey Project.

Wallace, R. (2014). The Influence of Cognitive Distortions on the Social Mobility and Mental Health of African Americans. The Odyssey Project Research Journal.

Wallace, R. (2015). Collective Dominative Cognitive Bias Syndrome. The Odyssey Project Journal of Scientific Research.

Wallace, R. (2015). The Miseducation of Black Youth in America: The Final Move on the Grand Chessboard. Etteloc Publishing.

Wallace, R. (2016). African Americans & Depression: Denying the Darkness. The Odyssey Project Research Journal .

Wallace, R. (2016). Molestation, Incest, and Rape in African-American Families. The Odyssey Project.

Wallace, R. (2016). Racial Trauma & African Americans. The Odyssey Project.

Wallace, R. (2016). Special Education Disproportionality Position Paper. The Odyssey Project.

Wallace, R. (2017). Born in Captivity: Psychopathology as a Legacy of Slavery. Houston: Odyssey Media Group & Publishing House.

Welsing, F. C. (1970). The Cress Theory of Color Confrontation and Racism: A Psychogenetic Theory and World Outlook. Washington, DC: C-R Publishers.

Welsing, F. C. (1990). The Isis Papers. New York: Third World Press.

Wexler, L. (2009). The Importance of Identity, History, and Culture in the Wellbeing of Indigenous Youth. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 1-2.

Williams, H. A. (2016). “How Slavery Affected African American Families” Freedom’s Story. National Humanities Center.

Williams, W. (2015). Most Serious Problems fro Blacks Rooted in Culture, Not Racism. The Citizen.

Wilson, T. L., & Banks, B. (1994). A Perpsective on the Education of African American Males. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 97-100.

Yael Danieli, P. (1997). International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. The National Center for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, 1.

Zabel, R. H., & Nigro, F. A. (1999). Juvenile Offenders with Behavioral Disorders, Learning Disabilities, and No Disabilities: Self-reports of Personal, Family, and School Characteristics. Behavioral Disorders, 22-40.